Introduction

As a convenient avenue for communication, social network platforms facilitate the establishment and maintenance of social networks (

Jackson & Wang, 2013). On social network platforms, individuals can keep in touch with their existing friends and meet new friends (

Ellison et al., 2007,

2011). Although online interactions are often considered an extension of offline social activities (

Tosun & Lajunen, 2010), some people tend to manipulate the information they post online to create a virtual identity that is partially or even totally different from their identity in the offline world, which is referred to as online identity reconstruction (

Hu et al., 2015).

Some people reconstruct their identity online because of vanity (

Hu et al., 2015). They want to attract attention and gain admiration from others. For example, a poor man could pretend to be rich by posting a picture of himself wearing an expensive watch. Some people want to gain bridging social capital online (

Hu et al., 2015). Reconstructing their online identity may provide them new chances to make friends with people from different backgrounds. Disinhibition and privacy concerns are also important reasons for online identity reconstruction (

Hu et al., 2015). A reconstructed identity (such as an identity with a fake name) protects an individual’s privacy and makes him or her feel less inhibited online. The extent of online identity reconstruction varies from one person to another.

Given that some aspects of identity are intangible (such as beliefs and values;

Hitlin, 2011), people usually communicate their identity through embodied self-presentation (

Schau & Gilly, 2003). For example, a person can express his or her belief by quoting a meaningful sentence in the online profile. Although some studies have investigated people’s identity and self-presentation on social network platforms (e.g.,

Kapidzic, 2013;

Krämer & Winter, 2008;

Lee et al., 2014;

Ong et al., 2011;

Rosenberg & Egbert, 2011;

Seidman, 2013), not much research focused on online identity reconstruction. Although two existing studies have explored the motivations for online identity reconstruction (

Hu et al., 2015;

Huang et al., 2018), they were limited to a single culture.

It has been suggested that culture has a significant influence on people’s online self-presentation (

Chu & Choi, 2010;

Cooley & Smith, 2013;

Kim & Papacharissi, 2003;

Rui & Stefanone, 2013;

C. Zhao & Jiang, 2011). For instance, it is suggested that Singaporean users share significantly more photos on social network platforms, whereas American users update their profiles with text-based content more frequently (

Rui & Stefanone, 2013). A prior study also found that American users posted more photos of social events (such as parties) to show their connections with numerous friends, whereas Russian users were more likely to post personal photos with family members (

Cooley & Smith, 2013). Cultural differences are clearly salient in the behavior associated with online identity reconstruction, but little effort has been made to investigate the effects of culture on motivations for online identity reconstruction. Therefore, more attention should be paid to explore whether people from different countries are motivated differently when they reconstruct their identity on social network platforms.

In addition, previous research on cultural differences mainly focused on usage patterns (such as the intensity of use) and self-presentation behavior (such as profile management and self-presentation strategies) on social network platforms. Indeed, there is a lack of research when it comes to exploring cultural differences in online identity reconstruction. Considering this, this study aims to explore cultural differences in motivations for online identity reconstruction between China and Malaysia.

Given that the motivations for online identity reconstruction were proposed on the basis of a Chinese sample (

Hu et al., 2015), China was thus selected as one of the target countries in this study. In addition, as a developing country with the highest proportion of Chinese in its population, Malaysia was selected as the other target country. The Malaysian-Chinese accounted for 22.8% of the total population of Malaysia (

Department of Statistics Malaysia [DOSM], 2019). Moreover, China and Malaysia have a similar level of economic development and the pervasiveness of social media. The national wealth was considered when selecting the target countries because national culture is significantly correlated with national wealth (

Baptista & Oliveira, 2015). Furthermore, 65% of the Chinese population and 75% of the Malaysian population use social media actively (

We Are Social, 2018). The similarities in the level of economic development and social media usage rate reduce the uncertainties of comparing the behavior of Chinese and Malaysian social network platform users.

Previous research suggested that people may be driven by motivations like vanity, bridging social capital, disinhibition, and privacy concerns when they reconstruct their identity online (

Hu et al., 2015). Although studies related to these factors have been conducted in China (

Mo & Leung, 2015;

N. Zhou & Belk, 2004;

T. Zhou & Li, 2014), as well as in Malaysia (

Almadhoun et al., 2012;

Balakrishnan, 2015;

Chui & Samsinar, 2011;

Helou, 2014;

Mohamed & Ahmad, 2012), none of these studies made comparisons between Chinese and Malaysian people. It is not clear whether users from China and Malaysia are motivated differently by the above-mentioned factors when they reconstruct their online identity. The multiracial society of Malaysia provides good opportunities for comparisons between not only the Chinese with the Malaysians but also different ethnic groups (such as the Malaysian-Chinese and the Chinese from China). The comparisons of different ethnic groups may offer deeper insights into the effects of culture. Therefore, this study tries to resolve the following research questions:

Research Question 1: What are the motivational differences between Chinese and Malaysian social network users in online identity reconstruction?

Research Question 2: What are the motivational differences between users from different ethnic groups (the Malaysian-Malays, the Malaysian-Chinese, and the Chinese from China)?

Results

Hypotheses Testing

To capture an overall picture of the cultural differences, we first analyzed the data collected from China and Malaysia as a whole. After this, we divided the Malaysian sample into three groups: the Malaysian-Malays, the Malaysian-Chinese, and Others (i.e., the Malaysian-Indians and the Malaysian-Others). We then analyzed the data collected from Chinese participants, the Malaysian-Chinese, and the Malaysian-Malays to examine whether people from different ethnic groups are motivated differently. Because the main focus of this study is Chinese and Malaysian culture, the Malaysian-Indians and the Malaysian-Others were excluded in the analysis of ethnic groups.

It has been suggested that parametric tests (such as

t test and analysis of variance [ANOVA]) could be used with Likert-type scale data (

Elliott & Woodward, 2007;

Norman, 2010;

Pallant, 2007). Parametric tests are robust to violations of test assumptions (

Norman, 2010). Previous researchers found that parametric tests are more powerful, except when the distributions of the data are the most nonnormal ones (such as mixed-normal distribution;

Rasmussen, 1989). Parametric tests have similar Type I error rate with nonparametric tests (

Gregoire & Driver, 1987), but have lower Type II error rate (

Rasmussen, 1989). Therefore, we used parametric tests in this study.

T test and ANOVA were conducted to analyze the data.

Table 5 summarizes the results of

t test.

As shown in the table, Malaysian participants scored significantly higher on all the physical vanity items than Chinese participants. This suggests that, in comparison with Chinese participants, Malaysian participants were more likely to reconstruct their identity to increase their physical attractiveness on social network platforms. Therefore, H1 was supported. However, there was no significant difference in achievement vanity, except that Chinese participants showed greater concern in comparing their own success with others’. Thus, H2 was not supported. In addition, Chinese participants scored significantly higher on all the bridging social capital items than Malaysian participants, indicating that Chinese participants were more inclined to be motivated by bridging social capital during identity reconstruction on social network platforms, aiming to meet new friends and build various new social connections. Therefore, H3 was supported. Moreover, Chinese participants scored significantly higher on all the disinhibition items than Malaysian participants, suggesting that Chinese participants were more inclined to be motivated by the online disinhibition effect (both benign and toxic disinhibition) when reconstructing their identity online. Therefore, H4 and H5 were supported. Meanwhile, when compared with Chinese participants, Malaysian participants scored significantly higher on privacy concern items, indicating that Malaysian participants were more inclined to reconstruct their identity for the purpose of protecting their privacy on social network platforms. Therefore, H6 was supported.

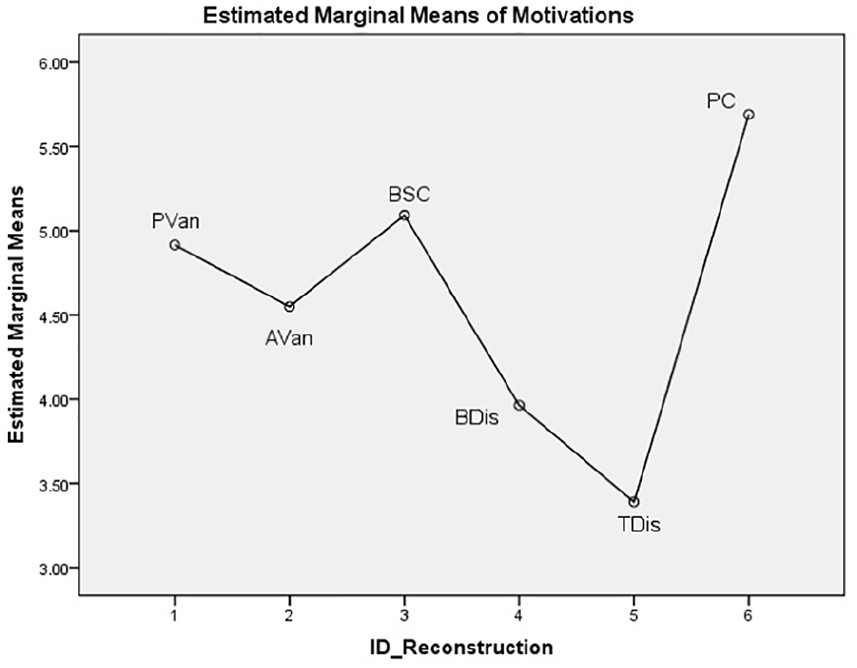

In addition to examining the differences between Chinese and Malaysian participants, the repeated measure one-way ANOVA was performed to examine whether participants from the same country weight these motivations differently and which motivation is more important for them. The results revealed significant differences in the weight of the motivations in the Chinese sample,

F(3.278, 1366.877) = 44.259,

p < .001, η

2 = 0.096. Specifically, Chinese participants had significantly higher mean scores on bridging social capital than on other motivations (as shown in

Figure 1), thus indicating that bridging social capital was more important than other motivations for the Chinese participants when they reconstruct their online identity.

In the Malaysian sample, significant differences were also found in the weight of the motivations for online identity reconstruction,

F(4.221, 1671.506) = 191.409,

p < .001, η

2 = 0.326. Specifically, all the differences between different motivations were significant. As shown in

Figure 2, privacy concern was the most important motivation for the Malaysian participants.

Ethnic Groups

We also made comparisons between different ethnic groups (the Chinese-Chinese, the Malaysian-Chinese, and the Malaysian-Malays). The results (as shown

Table 5) indicated that, in comparison with Malaysian-Chinese participants, Chinese-Chinese participants scored significantly higher on all the items of bridging social capital, toxic disinhibition, one of the two benign disinhibition items, and scored significantly lower on all the items of privacy concerns. However, there were no significant differences in physical vanity and achievement vanity between the Malaysian-Chinese and the Chinese-Chinese. In addition, the Malaysian-Malays scored significantly higher on the items of physical vanity and bridging social capital than the Malaysian-Chinese. The Malaysian-Chinese had similar mean scores with the Malaysian-Malays on the remaining motivations (i.e., achievement vanity, begin and toxic disinhibition, and privacy concerns).

Discussion

This study examined cultural differences in the motivations for online identity reconstruction. Significant differences have been identified between Chinese and Malaysian participants. The results revealed that, when compared with Chinese participants, Malaysian participants were more inclined to be motivated by physical vanity during online identity reconstruction. Previous research suggested that Malaysian people are less satisfied with their body image than Chinese people (

Swami et al., 2013). This dissatisfaction may drive Malaysian participants to pay more attention to beautifying their physical appearance during online identity reconstruction.

However, there was no significant difference in achievement vanity. A possible explanation for the similarity on achievement vanity may be that achievement vanity is becoming increasingly prominent in both China and Malaysia. Previous research postulated that Chinese people are strongly motivated by achievement vanity (such as reputation and success) when they buy luxury goods (

N. Zhou & Belk, 2004). Similarly, Malaysian people also prefer products that display social status (

Chui & Samsinar, 2011). In addition, both Chinese and Malaysian people are eager to show off their achievements on social network platforms. Chinese participants were found to employ competence strategy in online self-presentation to show their abilities, accomplishments, and performance (

Chu & Choi, 2010), whereas Malaysian users tend to promote their achievements on social network platforms to build a positive self-image (

Abdullah et al., 2014).

As hypothesized, Chinese participants were more inclined to be motivated by bridging social capital than Malaysian participants during identity reconstruction on social network platforms. As proposed by

Chang and Zhu (2011), China is a relation-based society and Chinese people believe that it is important to establish various relationships (

Chang & Zhu, 2011). This finding is consistent with

Mo and Leung’s (2015) study which suggested that Chinese users are driven by the need for meeting new friends on social network platforms. This result adds knowledge to existing research by identifying the differences in the motivation of bridging social capital between Chinese and Malaysian social network users (

Almadhoun et al., 2012;

Helou, 2014;

Mo & Leung, 2015).

In addition, Chinese participants are more inclined to be motivated by disinhibition (both benign and toxic disinhibition) than Malaysian participants during online identity reconstruction. Previous studies suggested that people feel less inhibited online and express themselves freely (

Bargh et al., 2002;

Lapidot-Lefler & Barak, 2015). The finding regarding benign disinhibition is consistent with existing research which indicated that Chinese users tend to disclose their feelings, opinions, and experiences to a greater extent on social network platforms when the level of perceived anonymity is high (

X. Chen et al., 2016). The finding regarding toxic disinhibition is in line with the findings of a survey administered in 25 countries, which indicated that the cyberbullying rate among youth was much higher in China than in Malaysia (

Microsoft, 2012), and toxic online disinhibition was positively associated with overall cyberbullying behavior (

Udris, 2014).

Moreover, there was a significant difference in privacy concerns. Malaysian participants were more inclined to be motivated by privacy concerns than Chinese participants during identity reconstruction on social network platforms. Previous research found that people with a high level of uncertainty avoidance showed a more prominent preference for stability, predictability, greater risk avoidance, and discomfort with unknown futures (

Hofstede, 1980). The finding of this study is consistent with previous studies which postulated that individuals from higher uncertainty-avoiding cultures (e.g., Malaysian people) are more sensitive to potential losses (

Bontempo et al., 1997) and perceive a higher level of risks (

Al Kailani & Kumar, 2011). The results also support

Mohamed and Ahmad’s (2012) finding that Malaysian people who feel vulnerable about information loss tend to have greater concerns over privacy.

In addition to comparing participants from different countries (i.e., China and Malaysia), this study also investigated whether participants from the same country weight the motivations for online identity reconstruction differently. It was found that, for the Chinese participants, they placed more emphasis on bridging social capital than on other motivations, This is in line with a prior study which found that Chinese people paid much attention to personal connections (

X. P. Chen & Chen, 2004). For the Malaysian participants, among all the aforementioned motivations, they focused more on privacy concerns. It is consistent with previous research which suggested that Malaysian people are concerned about privacy issues when using online services (

Lallmahamood, 2007;

Mohamed & Ahmad, 2012;

Rezaei & Amin, 2013).

Ethnic Groups

The cultural differences were further investigated by examining the differences between ethnic groups (i.e., the Chinese-Chinese, the Malaysian-Chinese, and the Malaysian-Malays). It was found that participants from different ethnic groups were also motivated differently. Specifically, when compared with the Malaysian-Chinese, the Chinese-Chinese were more inclined to reconstruct their identity for bridging social capital and disinhibition (both benign and toxic disinhibition), but less likely to be driven by privacy concerns. Moreover, the Malaysian-Malays were more inclined to reconstruct their online identity due to physical vanity and bridging social capital than the Malaysian-Chinese.

An interesting finding was that the Malaysian-Chinese participants were less motivated by bridging social capital than the Chinese-Chinese and the Malaysian-Malays. The language might be a barrier that makes the Malaysian-Chinese participants less passionate in seeking bridging social capital. In Malaysia, people from different ethnic groups prefer their mother tongues. The Malaysian-Malays speak Bahasa Melayu (the Malaysian language), whereas the Malaysian-Chinese prefer Mandarin and Cantonese (

Wan Jafar, 2014). Although English is widely accepted as a second language, individuals face difficulties in communicating with people from other ethnic groups, because not everyone speaks English fluently (

Tan, 2005). The Malaysian-Chinese may be more likely to encounter linguistic difficulties than the Malaysian-Malays and the Chinese-Chinese because the dominant group in Malaysia is the Malaysian-Malays and the official language is

Bahasa Melayu (

Wan Jafar, 2014), whereas in China, most people speak Mandarin (

Odinye, 2015). The linguistic advantages are likely to facilitate the process of gaining bridging social capital for the Chinese-Chinese and the Malaysian-Malays, making them more motivated by bridging social capital in online identity reconstruction, although this needs to be verified in future research.

The motivational differences between the Chinese-Chinese participants and the Malaysian-Chinese participants were nearly consistent with those between the Chinese and the Malaysian (as a whole) samples. However, the differences in motivations for identity reconstruction between the Malaysian-Malay participants and the Malaysian-Chinese participants were not consistent with and not as salient as those between the Chinese and the Malaysian (as a whole) samples. The similarities between the Malaysian-Chinese participants and the whole Malaysian sample could be explained by the efforts that the Malaysian government has made to improve the harmony and unity of all ethnic groups, such as balancing economic disparity and political rights (

Tamam, 2009). In the multi-ethnic environment of schools, students are able to understand and communicate with peers from other ethnic groups (

Tamam, 2009). In a study concerning national identity, nearly 40% of the Malaysian-Chinese participants weighted their national identity (a Malaysian) over racial identity (a Malaysian-Chinese;

Tamam, 2011). Although the Malaysian government endeavors to promote the unity of different ethnic groups, some fundamental differences between the Malaysian-Chinese and the Malaysian-Malays are difficult to integrate, such as language and religion (

Noor & Leong, 2013). Although most Malaysian-Malays practice Islam, the Malaysian-Chinese follow different religions (such as Buddhism, Taoism, or other traditional Chinese folk religions;

Keshavarz & Baharudin, 2009). Religious beliefs may have some influences on personal values and behavior (

Bernardo et al., 2016;

Mohd Suki & Mohd Suki, 2015).

Theoretical and Practical Implications

This study has several contributions to the body of knowledge. This study provides a deeper insight into the motivations for online identity reconstruction by taking into account national culture. The findings suggested that participants from different countries are motivated differently during online identity reconstruction. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that vanity and disinhibition have been investigated in a cross-cultural context. This study also adds knowledge to the cross-cultural research concerning social network platforms. Most existing cross-cultural research concerning social network platforms compared cultural differences from the perspective of individualism versus collectivism (e.g.,

Kim & Papacharissi, 2003;

Rui & Stefanone, 2013;

C. Zhao & Jiang, 2011). By taking into account multiple cultural dimensions, this study provides a better understanding of the cultural dimension framework. Furthermore, this study sheds light on the specific differences between Chinese and Malaysian users. This study not only compared the Chinese participants with the Malaysian participants but also compared participants from different ethnic groups (e.g., the Malaysian-Chinese and the Malaysian-Malays).

Practically speaking, the findings of this study can provide directions in identifying the particular needs of different users, thereby social network platform practitioners can improve their services accordingly. The findings of this study would be especially beneficial for the companies that provide social networking services in both China and Malaysia (such as WeChat). Based on the results of this study, practitioners could deploy specific strategies to better serve social network platform users from different countries. They are suggested to place emphasis on different aspects when providing services to Chinese and Malaysian users. For example, the results indicated that the Chinese users focus more on bridging social capital and disinhibition than the Malaysian users, whereas the Malaysian users pay more attention to physical vanity and privacy than the Chinese users during online identity reconstruction. Therefore, it might be a good choice for the practitioners to enhance the features that facilitate the formation of bridging social capital (e.g., new friend recommendation) and free self-disclosure in the Chinese market; at the same time, said practitioners could highlight the features related to the presentation of physical attractiveness (such as photo editing service) and privacy protection (such as privacy setting) in the Malaysian market.

For the social network platform companies which mainly serve the Chinese users (such as QQ and Sina Weibo), more attention should be paid to help users gain bridging social capital because it is the most important motivator of online identity reconstruction for the Chinese users. For the social network platform companies whose service is available in Malaysia (such as Facebook), it is important to make users feel that their privacy is being protected because the Malaysian users are more concerned about their privacy during online identity reconstruction.

Moreover, the findings of this study can be meaningful for practitioners in other domains. In addition to social network platforms, the providers of other services may also find this study valuable. For example, when a company wants to extend its services to the Malaysian market (such as mobile pay services), it should pay more attention to protecting users’ privacy. Because the findings in the current study revealed that Malaysian people are more worried about their privacy on social network platforms, it is likely that they will also be concerned about privacy when using other online services. In addition, the results revealed that Chinese people focus more on bridging social capital. Therefore, the integration of social networking features into other services (such as online shopping applications) may make the services more attractive to Chinese users. Moreover, marketers can deliver customized advertisements to different users based on their cultural background, thereby making the advertisements more effective.

Limitations and Future Research

While contributing to the literature about online identity reconstruction and cross-cultural research, the current study also has limitations. Although Hofstede’s cultural dimension framework provides a foundation for cross-cultural research, it is not free from criticism. For example,

Ess and Sudweeks (2005) questioned the generalizability of Hofstede’s results because the data were collected from a single organization. There are also concerns over cultural changes. It is uncertain whether Hofstede’s data are still reliable for representing contemporary reality (

Inglehart & Baker, 2000). Although most of the findings in this study are in line with Hofstede’s framework, future research is recommended to combine the framework with other theories to elicit more comprehensive insights about online identity reconstruction.

In this study, the participants were recruited using online surveys. However, the number of online users is large, and there are many “lurkers” who only read posts and do not make their presence known to others. It is often difficult to obtain comprehensive knowledge about the target population and track the nonresponse rate (

Andrews et al., 2003). Considering the disadvantages of convenience sampling method, the findings of this study may have limited generalizability. Future studies are suggested to use probability sampling methods to validate the results and generalize the findings to a broader population. Given that the authors cannot speak the Bahasa Melayu (the Malaysian language), we cannot ensure the quality of the questionnaire if it is translated into the Malaysian language. Therefore, English questionnaires were used in Malaysia. However, a questionnaire in the native language may help the participants understand the research better. The data in this study were collected at a specific point of time; thus, the limitations of cross-sectional studies should be considered when generalizing the findings. Future researchers could design a longitudinal study to examine whether people’s motivations change over time. At the same time, they can measure the outcomes of online identity reconstruction by comparing participants’ status before and after online identity reconstruction. Such a longitudinal study can reveal whether people obtain what they want (e.g., more bridging social capital) after reconstructing their online identity.