The Desirability of CSR Communication versus Greenhushing in the Hospitality Industry: The Customers’ Perspective

Abstract

Recent literature describes “greenhushing” as the deliberate managerial undercommunicating of corporate social responsibility (CSR) efforts for fear of negative customer opinions and responses. Based on social psychological theory of tourism motivation and cognitive dissonance theory, this research tries to seek evidence that justifies such a practice from the customers’ perspective. In study 1, focus groups reveal that hotels’ CSR communication and awareness creation for environmental issues are desired by consumers. In study 2, an online experiment uncovers that one-way and particularly two-way CSR communication lead to more favorable attitudes toward hotels’ CSR communication and lower intentions to behave unethically, compared with greenhushing. Perceived consumer effectiveness mediates the relationship between type of CSR communication and attitudes toward hotels’ CSR communication as well as intentions to behave unethically. Pro-environmental identity moderates the relationship. Taken together, our research provides little justification for greenhushing in a hospitality context from the customers’ perspective.

Introduction

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) refers to “the responsibility of enterprises for their impacts on society” (European Commission 2011, p. 6). CSR is still—and perhaps more than ever—a topic of crucial interest in business practice and scholarly business research (Sheldon and Park 2011). The literature generally agrees that CSR activities and their communication are increasingly important as well as in ever greater demand by socially conscious stakeholders. Among them, consumers are especially keen to demand socially and environmentally engaged behavior from companies, while pressuring them into stronger commitment to sustainability (Miller 2003; Grosbois 2012). However, recent tourism research has uncovered the managerial practice of “greenhushing” in the context of the hospitality industry. Greenhushing refers to the intentional undercommunicating of CSR activities by tourism businesses (Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017). This phenomenon arose as a solution allowing business owners and managers to reconcile the gaps between their understanding of customer expectations and their own sustainability policy (Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017). Stated differently, greenhushing stems from the businesses fearing that direct CSR communication may offend customers or may even provoke negative feedback (Coles et al. 2017). Yet, the literature on greenhushing has been not only scarce but has also focused primarily on the managerial perspective, leaving an important question unanswered: how do consumers actually perceive such practices?

Tourism has evolved into an increasingly significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions (Bojanic and Warnick 2019). Thus, not only business owners and managers but also tourists are responsible for the industry’s environmental performance (Ganglmair-Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft 2017). Prior research shows that tourists often pursue actions or show behaviors that may be environmentally damaging or deemed socially inacceptable as people behave differently at the tourist destination and at home (Ganglmair-Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft 2017; Juvan and Dolnicar 2017). The reason for this is that going on holiday is a self-indulgent act that might result from people feeling they have earned a special experience, including behaving lavishly in terms of resource consumption and responsible behavior (Carr 2002; Coles et al. 2017; Ganglmair-Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft 2017). Hence, it is understandable that, from a financial as well as an ethical point of view, a key challenge for hotel managers is curtailing this self-indulgent—often irresponsible—guest behavior without spoiling their holiday experience. Hotels increasingly try to do their part, by engaging in CSR that reduces the businesses’ impact (Coles et al. 2017). However, in order to achieve this aim, tourists might also need to be encouraged to behave more sustainably and responsibly so that the industry as a whole can become more sustainable (Juvan and Dolnicar 2017).

The primary aim of this study is to investigate whether the hospitality practitioners’ assumption about greenhushing holds true—does hotels’ CSR communication really disturb their guests during their stay? More specifically, relying on social psychological theory of tourism motivation (Iso-Ahola 1982) and cognitive dissonance theory (Festinger 1962), we try to address the following questions: (1) How do tourists actually perceive hotels’ CSR activities in general, and CSR communication in particular; and (2) how does greenhushing, compared with CSR communication, affect tourists’ attitudes and behavioral intentions? In addition, we explore the roles of perceived consumer effectiveness and pro-environmental identity when tourists build their attitudinal and behavioral responses to CSR communication. To this end, we employ a mixed method approach by conducting focus groups (study 1) and an experiment (study 2).

The contributions of this research are twofold. First, our findings should serve as one of the pioneering studies that examine greenhushing from the customers’ perspective. Thus, our research will help industry practitioners make more balanced decisions regarding such a strategy. Second, applying a dual framework composed of the social psychological theory of tourism motivation and cognitive dissonance theory, we try to theorize consumers’ attitudinal and behavioral reactions toward greenhushing, compared with CSR communication. In so doing, we also examine the mediating and moderating roles of perceived consumer effectiveness and pro-environmental identity in this research context.

In what follows, we first explain the background of our research, greenhushing and CSR communication. Then, we build our theoretical framework based on the social psychological theory of tourism motivation and cognitive dissonance theory, while formulating a series of hypotheses. Next, we describe study 1 and study 2 in detail and draw overall implications. In closing, we recognize major limitations of the study and make future research suggestions.

Background

Greenhushing

CSR communication is often seen as a logical device for informing stakeholders of the social and environmental sustainability efforts a company undertakes (Brønn and Vrioni 2001; Pérez and Rodríguez del Bosque 2014). CSR communication not only creates positive impressions in the minds of relevant stakeholders, but also “becomes central to the enactment of taking responsibility for being sustainable” (Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017). CSR communication helps sensitize people and encourages them to perceive and understand fully the effects of their behavior while on vacation.

However, recent studies (Coles et al. 2017; Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017) point to a different direction—“greenhushing,” which is the deliberate undercommunicating of CSR activities. Greenhushing is a term coined anecdotally by Stifelman (2008) and academically by Font, Elgammal, and Lamond (2017) to allude to a contrasting concept to “greenwashing.” Both greenwashing and greenhushing are forms of a sustainability marketing strategy, whose “primary goal is to sell more products without regard for the limits to growth theses while shrouding itself in the cloak of social responsibility” (Kilbourne 2004, p. 201). Delmas and Burbano (2011) refer to companies that greenhush as “silent green firms,” while Ginder, Kwon, and Byun (forthcoming) term such a strategy the “discreet CSR position.” For Vallaster, Lindgreen, and Maon (2012), greenhushing firms are “quietly conscientious” and do not make sustainability part of their brand.

Greenhushing appears to be driven by several motivations. As aforementioned, greenhushing has its roots in greenwashing in that it is the fear of being accused of greenwashing by activists that drives companies to remain silent, despite actually being engaged in CSR (Vallaster, Lindgreen, and Maon 2012; Lindsey 2016; Ginder, Kwon, and Byun, forthcoming). Carlos and Lewis (2018) call this “hypocrisy avoidance,” the idea being that strategic silence prevents inconsistent attributions, particularly when the company has shown behavior that contradicts their environmental certification claims. The second reasoning provided for greenhushing is that customers simply do not care about CSR engagement (Vallaster, Lindgreen, and Maon 2012; Melissen et al. 2016) or CSR certification (Reiser and Simmons 2005). Thirdly, according to Coles et al. (2017) and Font, Elgammal, and Lamond (2017), in the context of the hospitality industry, greenhushing occurs because hotel managers believe that people on vacation might not want to hear about CSR activities undertaken to tackle global problems, such as resource depletion, climate change, or unsustainable lifestyles; instead, their guests want to behave indulgently on holiday, stepping out of their everyday-life responsibilities (Coles et al. 2017; Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017).

As empirical evidence, Font, Elgammal, and Lamond’s (2017) study examined 31 accommodation businesses in the Peak District National Park, UK, certified by the Environmental Quality Mark (EQM) audit. The EQM certification requires explicit environmental practice, including sustainability communication to consumers. A comparison between the EQM audit reports and what was actually stated on the websites of these 31 businesses revealed that the hotels selectively communicated only a small proportion of their CSR activities—only 407 out of the 1,389 sustainability statements included in the EQM audit reports. The subsequent interviews with the business owners and managers suggest that, because the EQM certification serves as “a symbolic legitimacy boundary,” in the practical setting, they tend to undercommunicate their CSR activities in order to “mitigate a potential disconnection between their perception of customer expectations and their own operational position concerning sustainability issues” (Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017, p. 1008).

As the third stage of a large-scale research project with small- and medium-sized tourism enterprises (SMTEs) in South West England, Coles et al. (2017) interviewed 20 managers and owners of 16 businesses and discussed how environmental resources featured in their business models. The SMTEs included hotels, bed-and-breakfast establishments, self-catering facilities, and group accommodation providers. Their findings suggest that CSR communication was seen as “at best superfluous, at worse potentially threatening to reputation and revenue” (Coles et al. 2017). Because of the emerging use of social media, their guests tend to interpret or assess green credentials very differently than they did in the past. Any “direct, assertive or prescriptive” messages may cause negative online reviews, which can be detrimental to reputation and revenue. In addition, the SMTE managers and owners seemed not only reluctant to disclose their CSR activities, but also tolerant of their guests wasting environmental resources. For example, those hotels adopting energy- or water-saving measures kept silent even when their guests used these resources so lavishly that costs approached the point of nullifying savings.

Font, Elgammal, and Lamond’s (2017) and Coles et al.’s (2017) research seems to suggest that, by greenhushing, hotels want to shelter guests from the negative impacts of their hedonic consumption, avoiding the creation of cognitive dissonance and thus preventing the emergence of customer guilt. In the practitioners’ view, guests pay high prices for their comfort, which must not be compromised by asking guests to practice sustainability (Budeanu 2007; Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017).

Nevertheless, greenhushing may be as problematic as greenwashing as “it leaves the field open for pretenders” (Stifelman 2008). The absence of CSR communication, as an expression of strategic inaction, hinders the diffusion of socially and environmentally desirable activities (Carlos and Lewis 2018) and, thus, stifles the progress of the sustainability movement and of prosocial behavior (Ginder, Kwon, and Byun, forthcoming).

Consumer Responses to CSR Communication

The above discussion casts doubt on the effectiveness of greenhushing: does the hotels’ “silence about doing good” really produce both happy guests and sustainable tourism? In fact, as per the vast literature on CSR communication (e.g., Morsing and Schultz 2006; Pérez and Rodríguez del Bosque 2014; Diehl, Terlutter, and Mueller 2016), some may argue that consumers would actually prefer CSR communication to greenhushing, despite the practitioners’ beliefs reported in Coles et al. (2017) and Font, Elgammal, and Lamond (2017).

We expect that issuing CSR communication, in contrast to non-CSR communication, will result in a more favorable attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication, thus not pointing toward the “I-don’t-want-to-hear-about-it” rationale. This could be driven by cognitive processes, considering that it can be expected that consumers know that acting sustainably and responsibly is objectively seen as the right thing to do (Ganglmair-Wooliscroft and Wooliscroft 2017). Moreover, besides the initial necessary awareness or attention to issues desired by any marketing or corporate communication (Batra and Keller 2016), a spill-over effect could occur in that the “good” behavior of companies could directly spill over to guests, triggering a similar “good” attitude or even behavior in the customers.

However, we wonder whether consumers’ attitudes and behavioral intentions vary according to how CSR communication is framed. We address this question by probing two types of CSR communication strategy as suggested by Morsing and Schultz (2006): (1) “one-way CSR communication,” which only informs stakeholders about what the company does in the pursuit of CSR; and (2) “two-way CSR communication,” which tries to involve the stakeholders in the pursuit of CSR. According to Morsing and Schultz (2006), two-way CSR communication should be preferred to one-way CSR communication, as consumers can actively collaborate with the company to improve CSR efforts. Stated differently, two-way CSR communication is more in line with consumer social responsibility, defined as the “conscious and deliberate choice to make consumption choices based on personal and moral beliefs” (Devinney et al. 2006, p. 3) as, after all, tourists should “both consume and constitute responsible tourism” (Caruana et al. 2014). In this vein, two-way CSR communication should be specific about the behavior to be modified (Juvan and Dolnicar 2017).

This study attempts to contrast these two types of CSR communication with “non-CSR communication,” which is a proxy for greenhushing. For consumers, non-CSR communication and greenhushing appear very similar. After all, consumers cannot differentiate between the “apathetic CSR position,” which refers to a silent position because companies do not engage in CSR and the “discreet CSR position,” which refers to companies that engage in CSR but do not communicate about it (Ginder, Kwon, and Byun, forthcoming).

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses

In this section, we formulate a series of hypotheses based on a dual theoretical framework, combining social psychological theory of tourism motivation (Iso-Ahola 1982) and theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1962).

First, people usually go on holiday to enjoy luxury, freedom, and something they cannot afford or would not do in their daily lives (Malone, McCabe, and Smith 2014; Coles et al. 2017). Holiday tourism is a hedonic activity, where the pursuit of pleasure, fun, and excitement as consumption experience is paramount (Gnoth 1997; Bigné, Mattila, and Andreu 2008). Such behavior is theoretically explained by Iso-Ahola’s (1982) social psychological theory of tourism motivation. According to this theory, in addition to the search for personal and interpersonal rewards, it is the need to escape from everyday personal and interpersonal environments that motivates people to go on holiday. The escape from the personal world includes escaping from personal troubles, problems, and difficulties and the escape from the interpersonal world pertains to escaping family, friends, and coworkers (Iso-Ahola 1982). We extend this idea by claiming that when going on holiday, one may also escape from one’s personal responsibilities and from the problems of the world, such as climate change, resource consumption, or social concern for other people.

There is ample evidence in research that lends support to the social psychological theory of tourism motivation in a tourism context; that is, tourists’ behavior while on holiday differs from their behavior at home (Carr 2002; Stanford 2008; Dolnicar and Grün 2009; Barr, Shaw, and Coles 2011). Broadly speaking, this behavioral change becomes manifest in “typical” tourist behaviors, for example, sleeping longer, sightseeing, indulging in elaborate meals, or doing sports. However, it also shows in one’s laxness concerning responsible behaviors (Dann and Cohen 1991). People might also see no financial incentive to conserve natural resources, justifying lavish behavior with a “because I’ve paid for it” rationale, regardless of the morality of their actions (Miller et al. 2010). Dolnicar and Grün (2009) find that both actual actions of and moral compliance with pro-environmental behavior are lower on holiday than at home. Similar findings come from Juvan and Dolnicar (2014), who reported that a similar inconsistency even applied to some environmental activists. Furthermore, the carbon footprint of Dutch travelers has been found to become twice as high as at home (Bruijn et al. 2013). On holiday, people also eat more environmentally damaging food than they normally do (Gössling et al. 2011). Coles et al. (2017) find recycling to be the most commonly suspended practice among tourists.

Second, whether deliberate self-indulgence or unintended hedonism, any tourist behavior may result in negative environmental and social impacts. Since discouraging people from going on vacation is not an option, hotels need different approaches to reducing irresponsible behavior without disturbing, annoying, or upsetting guests (Juvan and Dolnicar 2017; Buckley 2018). The theory of cognitive dissonance proposes that individuals dislike experiencing a situation involving conflicting attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors, which may cause emotional disturbance and mental discomfort (Festinger 1962). In our study context, such a situation occurs in the aforementioned examples of the social psychological theory of tourism motivation—tourists are inclined to behave extravagantly while on holiday, often acting in a manner that is inconsistent with their sustainable behavior at home. Frequently, this discrepancy might be suppressed in the special, hedonic context of a holiday (Dolnicar, Knezevic Cvelbar, and Grün 2017).

In this case, CSR communication could serve as an instrument to make salient this discrepancy between holiday behavior and everyday beliefs. Cognitive dissonance would occur when individuals act less sustainably on vacation while feeling internal conflicts with their daily beliefs. Thus, as a way of resolving such dissonance, CSR communication could lead guests to adapt their attitudes or their behaviors. In particular, two-way CSR communication explicitly addressing sustainable activities and requesting customers’ proactive involvement is likely to, first, create strong cognitive dissonance and, second, enhance the attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication and decrease the intention to behave unethically, as ways to reduce the mental discomfort and restore balance. We therefore posit:

Prior research indicates that perceived consumer effectiveness—defined as “the consumer’s perception of the extent to which their actions can make a difference in solving environmental problems” (Akehurst, Afonso, and Martins Gonçalves 2012, p. 976)—directly affects environmentally or socially conscious consumer behavior (Kang, Liu, and Kim 2013). Also, perceived consumer effectiveness strengthens consumers’ proactive concerns regarding the environment, their purchase intentions for sustainable products, as well as their socially responsible behaviors (Webster Jr. 1975; Ellen, Wiener, and Cobb-Walgren 1991; Antonetti and Maklan 2014; Currás‐Pérez et al. 2018). These findings imply that perceived consumer effectiveness may contribute to resolving the inconsistency between holiday and everyday behaviors.Hypothesis 1a: Compared with non-CSR communication, both one-way and two-way CSR communication positively affect the attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication.Hypothesis 1b: Compared with non-CSR communication, both one-way and two-way CSR communication negatively affect the intention to behave unethically.Hypothesis 2a: Compared with one-way CSR communication, two-way CSR communication more positively affects the attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication.Hypothesis 2b: Compared with one-way CSR communication, two-way CSR communication more negatively affects the intention to behave unethically.

On holiday, guests might feel that they have less control over responsible behaviors, seeing that the exceptional surroundings present obstacles to behaving in a manner that is as ethically correct and responsible as at home (Juvan and Dolnicar 2017). By addressing exactly how customers can help the hotel find a path toward more sustainable tourism, if hotels can identify specific actions they can control, two-way CSR communication will lead to a higher level of perceived consumer effectiveness, compared to one-way CSR communication. This increased perceived consumer effectiveness might in turn lead consumers to better understand how they can act on their own responsibility. Thus, strengthening perceived consumer effectiveness via CSR communication might open up a path allowing guests to reduce their mental discomfort, since their proactive involvement in CSR activities can reduce such discomfort connected to cognitive dissonance. Following this logic, we believe that two-way CSR communication is more effective in generating a more positive attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication and mitigating the intention to behave unethically, compared with non-CSR communication and one-way CSR communication. This effect is mediated by perceived consumer effectiveness. In short, we posit that the relationship between the type of CSR communication (i.e., non-CSR communication group, one-way CSR communication group, and two-way CSR communication group) and the consumers’ attitudinal and behavioral reactions to it can be mediated by perceived consumer effectiveness. More formally:

As a large part of CSR pertains to sustainability efforts, we further expect that individuals’ pro-environmental identity will influence their attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication and intention to behave unethically while on holiday. Self-identity refers to how individuals see themselves and the labels they use to describe themselves, in relation to particular behaviors (Meijers et al. 2019). This construct leads one to act according to the values and norms of the social group and to find a means of differentiating oneself from others (Christensen et al. 2004). Self-identity entails “temporal interplay between social and personal self-identity working together as an organizing system in constructing who a person was, is and could become in the future” (Dermody et al. 2018, p. 334). There is ample support from literature that self-identity typically influences behavior (e.g., Biddle, Bank, and Slavings 1987; Grewal, Mehta, and Kardes 2000; Cook, Kerr, and Moore 2002; Stets and Biga 2003; Dermody et al. 2018; Meijers et al. 2019).Hypothesis 3: Perceived consumer effectiveness mediates the relationships between the type of CSR communication and (a) the attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication, as well as (b) the intention to behave unethically.

As part of one’s self-identity, pro-environmental identity expresses itself in an environmental-friendly consumption pattern and lifestyle (Dermody et al. 2018). The literature suggests that people with a higher level of pro-environmental identity respond better to CSR communication (Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017) and show more environmentally sustainable behavior (Thorbjørnsen, Pedersen, and Nysveen 2007; Whitmarsh and O'Neill 2010; Reed II et al. 2012; Steg et al. 2014; Dermody et al. 2015; Carfora et al. 2017; Juvan and Dolnicar 2017). It is this identity that manages coherence between consumers’ attitudes and behaviors to warrant “continuity across their experiences” (Dermody et al. 2018). Nevertheless, even for persons high in pro-environmental identity, a certain degree of desired self-indulgence and escapism from one’s responsibilities can occur. For example, prior research finds that even self-proclaimed environmental activists may display some attitude-behavior inconsistency concerning responsible behavior while on holiday (Juvan and Dolnicar 2014). As per the theory of cognitive dissonance, we can expect that the higher one’s pro-environmental identity, the smaller the attitude-behavior inconsistency, therefore the smaller the cognitive dissonance (Christensen et al. 2004; Whitmarsh and O'Neill 2010). More specifically, we expect that consumers who identify themselves as strongly pro-environmental will perceive hotels’ CSR communication more favorably, and will try to resist the temptation to act irresponsibly. On this basis, we contemplate:

To address these hypotheses, we conducted two studies: six semi-structured focus groups and an online between-subjects experiment.Hypothesis 4: Pro-environmental identity moderates the relationships between the type of CSR communication and (a) attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication, as well as (b) intention to behave unethically, in such a way that the relationships will be stronger for people high in pro-environmental identity.

Study 1: Focus Groups

Method

To gain initial insights on greenhushing from the customers’ perspective, we conducted six semi-structured focus groups. Focus groups as a research method are a form of interactive group interview, which strive to gather perceptions, concerns, and opinions relating to a particular area of interest in a relaxed setting (Malhotra 2019).

The study was conducted in Austria. The participants consisted of both university students and general consumers. We first contacted potential participants by e-mail via the university database that includes both students and nonstudents (adults and senior citizens enrolled in the lifelong learning programs). Seventy-five people responded to this query. We then chose only those who had stayed in at least one hotel within the last 24 months. In total, this left us with 40 participants. Taking into account the gender balance, we created six groups, each of which included six to nine participants. We tried to choose people with similar characteristics as homogeneous groups are likely to create a better communication atmosphere, and therefore respond to questions more truthfully (Schulz 2012). For all focus groups, we used a university classroom with a relaxing atmosphere.

Based on the literature on CSR communication in general, and the hospitality industry in particular, we prepared a discussion guideline for the moderator. At the beginning of the session, we broadly defined CSR using several examples in an attempt to ensure all participants had an equal minimum knowledge of CSR. During the discussion, we asked questions about holiday behaviors in general, the perception of CSR activities and CSR communication, and the desirable forms of CSR communication in the hospitality industry. One focus group session typically lasted 90-110 minutes. As an incentive, each participant received €10.

With the participants’ permission, the conversation was audio-recorded and transcribed for the analysis. The transcripts were coded by two independent coders according to the qualitative content analysis procedure developed by Mayring (2010). We recruited two junior faculty members from the marketing department and provided training for qualitative content analysis. Because of the nature of the study, the numerical intercoder reliability was not calculated. Nonetheless, the illustrative stories and anecdotes were carefully identified and interpreted through iterative discussions between the coders.

Results

We first asked the participants how they behave when they are away from home during their vacation. Our participants seemed to be in agreement that, on holiday, they act somewhat differently to how they would behave at home. Jonathan (19) said,

Participants mentioned a wide range of examples associated with their vacation behavior. However, we were particularly interested in what is deemed unethical or irresponsible. Many participants acknowledged that, on holiday, their behavior is less responsible than at home. Even Lisa (25), who presented herself as highly pro-environmental and prosocial, admitted to this, saying on holiday she cares less about the origin and nutritional value of food, for instance, although she still tries to act according to her convictions. The other participants said that, on holiday, they are unconcerned and “stop thinking” about their consumption decisions:I just think that there has to be a difference between daily life and holiday. Otherwise my holiday is no holiday, it’s just an ordinary day.

According to them, during the holiday, they feel less pressured by social rules or obligations.I think less about the consequences of my decisions. (Nina, 19)I am so anonymous, so I can do as I please. Nobody knows me, nobody talks to me. (Florian, 21)I think we tend to act less responsibly than at home. Flying is my personal weakness. I want to treat myself, I want to save time, I want to be more comfortable than at home. (Evelyn, 34)

Next, we addressed how tourists actually perceive hotels’ CSR activities in general, and CSR communication in particular. The participants of all six focus groups agreed that it is generally good to see that hotels are socially and environmentally engaged. Johanna (28) said,

Hotels’ CSR activities were considered laudable and welcome. At the same time, some thought that hotels are not engaged in enough CSR activities. Boris (63) said,Who else should care that things are being done ethically, besides companies and all of us, politicians, generally the people living on this planet? Considering hotels are a phenomenon of our society, they have got to play their part.

CSR communication was also perceived as positive, as long as hotels actually implement what is promised. Alice (24) said,Since the legal requirements are not there to rule out all irresponsible behavior, voluntary CSR commitment of hotels is absolutely necessary.

Lisa (25) echoed:Letting us know their CSR activities is good and necessary; otherwise you wouldn’t know what they do, unless they say it somewhere, highlighting what they value.

Then, we addressed what type of CSR communication accommodation businesses should use to influence guest behavior. Maria (26) thought that hotels should make consumers aware of ethical behavior:Yes, of course, hotels should communicate what they do! Transparency! Otherwise how would I know about it?

Similarly, for Kathrin (40), CSR communication serves as a good reminder to act responsibly:I think the hotel should make us more aware of these things. Many of us don’t yet have this sustainability and social thinking in our consciousness.

This seems to indicate that CSR communication reactivates tourists’ pro-environmental identity (that may have been forgotten) during the vacation. In this regard, Nina’s (19) statement was particularly poignant:I think those little card signs like “please save towels” are good … they remind you to pay more attention to certain things.

Also mentioned were little card signs displayed at all-you-can-eat buffet tables. Some participants thought they were useful when the signs indicate the provenance of foods. But there were some conflicting views on the signs asking to reduce food waste. According to Anna (30),Create big communication, big—so that it is seen! Don’t just write somewhere in very small letters “We are separating our waste,” but emphasize the message in bold capital letters! Being on holiday or not, we all realize that things are getting a little more critical with our environmental situation. We don’t want to hear about it but we should, in my opinion—see and hear it!

As aforementioned, since our participants seemed to favor hotels’ CSR communication, we specifically asked exactly what CSR activities hotels should not communicate. Here, answers were again diverse. For instance, Evelyn (34) said,The hotel should not say “please don’t take so much” but rather “go several times.”Sophie (26) echoed,I don’t want such signs at the buffet telling me I should not fill up my plate. We don’t want to be told what we have to do in our daily lives, so why would they do that to me during my holiday? In a supermarket, nobody tells me what I should buy.

Apart from “the obvious,” too much information was also somewhat off-putting. In Magdalena’s (32) opinion,There were things that were absolutely self-evident! I had the impression they doubt that I have a common sense!

One cautionary note was that CSR communication should avoid a tone of voice that is accusing or blaming:I don’t want too many details. And I don’t want to hear anything that goes into the direction of “we are so great,” either.

Anything that makes accusations—this I don’t want. That the receptionist comes to me and tells me how much CO2 I produced by coming here. No communication that’s pointing the finger. (Jonathan, 19)

Discussion

As a whole, our focus group results indicate that tourists’ behavior is indeed self-indulgent and less responsible during the vacation. Even a self-acknowledged pro-environmentalist recognized her irresponsible behavior while on vacation, although her belief in sustainability generally leads to rather responsible actions most of the time. Perhaps people tend to enjoy themselves more when they do not have to think about consequences or responsibilities.

In contrast to Font, Elgammal, and Lamond’s (2017) and Coles et al.’s (2017) managerial perspective, from the customers’ perspective, our participants find CSR activities highly important and consider CSR communication to be desired, laudable, necessary, and welcome. Indeed, some participants would even have preferred more explicit CSR communication—emphasizing customer awareness creation or even education—so that the sustainable values of a hotel could become more visible. This seems to support Del Chiappa, Grappi, and Romani’s (2016) claim that irresponsible tourist behavior can be rooted in excessively narrow communication activities. Hotels can step in and “think for” the consumers, whose environmental concerns tend to be switched off on holiday. In fact, as per some discussion comments, hotels’ reminders about a pro-environmental identity were actually welcome. However, hotels should address not only the “what” but also the “how,” without being too demanding or using an accusatory tone. These insights seem to collectively suggest that hotels should not be overly discrete in revealing their CSR activities, since, otherwise, their guests may never be able to find out about their goodwill, and ultimately feel misguided or disappointed (Parguel, Benoît-Moreau, and Larceneux 2011).

Study 2: Online Experiment

Method

Study 2 tests our hypotheses by running a between-subjects online experiment with three experimental groups. The first group is the one-way CSR communication group that receives communication about the hotel’s CSR activities, including information on the hotel’s solar panels on the roof to heat water, the hotel’s use of ecologically compatible detergents, the accessibility of all rooms for wheelchair users, and personal learning and development opportunities for employees, among others (Ettinger, Grabner-Kräuter, and Terlutter 2018).

The second group is the two-way CSR communication group that is encouraged to participate in, or respond to the hotel’s CSR activities. For example, we created a little card sign, as would commonly be found on a reception counter, saying: “We have installed solar panels on our roof to heat our water, but it is in your hands to use this precious resource responsibly. We only use ecologically compatible detergents, but it is up to you to decide how often you want your towels changed” (Ettinger, Grabner-Kräuter, and Terlutter 2018).

Finally, the third group is the non-CSR communication group, which is a proxy for greenhushing. This group does not receive any CSR-related communication, but corporate communication about the hotel’s history (adapted from a real hotel’s history description) only. This group serves as control group in the experimental setting.

Pretest

We conducted a pretest with 31 students for two purposes: (1) to run a manipulation check for our experimental stimuli and (2) to test the behavioral intentions scale. First, the respondents were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental groups: the baseline non-CSR communication group, one-way CSR communication group (CSR information without consumer involvement), and two-way CSR communication group (CSR information with consumer involvement). Next, the respondents were asked to rate two statements using a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree): (1) This text makes statements about the responsible behavior of guests, and (2) this text addresses corporate social responsibility (CSR) measures that I as a guest can support with my behavior. The two-way CSR communication group differed significantly from the other two groups regarding statement (1) (Mtwo-wayCSRcom = 6.11, SD = 1.62 vs. Mnon-CSRcom =1.73, SD = 1.56, p<.001, and Mone-wayCSRcom = 1.55, SD = 0.52, p<.001). The baseline group differed significantly from the other two groups regarding statement (2) (Mnon-CSRcom = 1.73, SD = 1.49 vs. Mone-wayCSRcom =3.73, SD = 1.85, p = .009 and Mtwo-wayCSRcom = 6.67, SD = 0.71, p<.001). The one-way CSR communication group differed significantly from the two-way CSR communication group (p<.001). Therefore, our manipulations were deemed successful.

We also tested the scale of intention to behave unethically while on holiday that was originally developed for the study. For the scale development process, we followed procedures reported by Jordan, Mullen, and Murnighan (2011) and Susewind and Hoelzl (2014). We created behavioral items connected to a winter ski and spa holiday (the setting provided for the participants before receiving the communication stimuli). This setting was deemed appropriate, as winter tourism is considered particularly crucial in climate change research (Gössling et al. 2012). Similar to Jordan, Mullen, and Murnighan (2011) and Susewind and Hoelzl (2014), several of such unethical, irresponsible holiday behaviors were distributed among a range of filler items related to typical winter holiday behavioral intentions (see Appendix). In this pretest, we examined the perceived degree of unethicality for all items (“How unethical do you consider the following descriptions?”: 7-point scale, 1 = not unethical at all, 7 = very unethical). We conducted principal components analysis on all items, unethical and filler items. A-four components solution was proposed. One component consisted solely of our unethical items; the other three components contained solely filler items. Hence, we indexed the three components with filler items and compared the means of our “unethical-items” component to the index of the filler items. The pretest was deemed successful, as the participants rated the “unethical-items” component significantly higher on the unethicality scale (M = 4.07, SD = 1.67) than the index of the filler items (M = 1.79, SD = 0.70, p<.001). The subscale of the six items making up the “unethical-items” component has high reliability with Cronbach’s α = .90.

Main Survey

The questionnaire consisted of two main sections. First, we asked the questions associated with perceived consumer effectiveness (4 items, adapted from Kang, Liu, and Kim 2013), intention to behave unethically (6 unethical behavioral items dispersed among filler items), pro-environmental identity (4-items, adapted from Whitmarsh and O'Neill 2010), and attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication (4 items, adapted from Lai and Li 2005). Second, we asked basic demographic questions, alongside a control variable that measured how much people generally liked winter holidays. All questions were written in German. The Appendix shows a complete list of the questionnaire items used in study 2.

We distributed the online questionnaire in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland via LimeSurvey (an online survey software) and Clickworker (a website that links the questionnaire to a consumer panel). In total, we recruited 601 respondents. The participants were randomly assigned to one of the three CSR communication scenarios (i.e., one-way, two-way, and non-CSR communication). No gender or age restrictions were applied. Respondents received an incentive of €1 for their participation.

Table 1 shows a summary of the respondents’ demographic profiles. The mean ages of the non-CSR communication, one-way CSR communication, and two-way communication groups are 36.37 (SD = 13.04), 37.22 (SD = 12.91), and 36.08 (SD = 12.46), respectively, with an overall mean of 36.58 (SD = 12.74). The differences in age were not significant across the groups.

| Profile | Non-CSR Communication (n = 198) | One-way CSR Communication (n = 212) | Two-Way CSR Communication (n = 191) | Overall (n = 601) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Male | 102 | 51.5 | 115 | 54.2 | 93 | 48.7 | 310 | 51.6 |

| Female | 96 | 48.5 | 97 | 45.8 | 98 | 51.3 | 291 | 48.4 |

| Educational level | ||||||||

| Ninth grade | 53 | 26.8 | 43 | 20.3 | 39 | 20.4 | 135 | 22.5 |

| Twelfth grade | 72 | 36.4 | 93 | 43.9 | 67 | 35.1 | 232 | 38.6 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 24 | 12.1 | 34 | 16.0 | 36 | 18.8 | 94 | 15.6 |

| Master’s degree | 44 | 22.2 | 40 | 18.9 | 45 | 23.6 | 129 | 21.5 |

| PhD degree | 5 | 2.5 | 2 | 0.9 | 4 | 2.1 | 11 | 1.8 |

| Monthly income | ||||||||

| Less than €500 | 20 | 10.1 | 26 | 12.3 | 27 | 14.1 | 73 | 12.1 |

| €501–€1,500 | 42 | 21.2 | 47 | 22.2 | 35 | 18.3 | 124 | 20.6 |

| €1,501–€2,500 | 36 | 18.2 | 41 | 19.3 | 31 | 16.2 | 108 | 18.0 |

| €2,501–€3,500 | 40 | 20.2 | 35 | 16.5 | 27 | 14.1 | 102 | 17.0 |

| More than €3,500 | 30 | 15.2 | 22 | 10.4 | 32 | 16.8 | 84 | 14.0 |

| Unknown | 30 | 15.2 | 41 | 19.3 | 39 | 20.4 | 110 | 18.3 |

Note: CSR = corporate social responsibility.

Results

For both dependent variables, that is, attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication and intention to behave unethically, we calculated separate models. For all multi-item variables in our study (the dependent variables and the moderator and mediator variables), we created compound variables by calculating the mean across all respective items. Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 2.

| Variables | Non-CSR Communication | One-way CSR Communication | Two-way CSR communication | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication | 5.162 | 1.353 | 5.607 | 1.278 | 5.707 | 1.261 | 5.492 | 1.317 |

| Intention to behave unethically | 4.641 | 1.304 | 4.015 | 1.311 | 3.777 | 1.163 | 4.145 | 1.312 |

| Pro-environmental identity | 4.759 | 1.358 | 4.758 | 1.229 | 4.945 | 1.218 | 4.818 | 1.271 |

| Perceived consumer effectiveness | 4.807 | 1.462 | 4.992 | 1.316 | 5.164 | 1.312 | 4.985 | 1.370 |

Note: CSR = corporate social responsibility.

Attitude toward Hotels’ CSR communication

To test hypothesis 1a, we calculated a separate analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the type of CSR communication as factor and attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication as dependent variable. Gender and general liking of winter holidays were included as control variables. An ANCOVA with planned contrasts is appropriate as, in both hypotheses 1a and 2a, we are interested in mean differences across our three experimental groups. The covariate gender was significantly related to attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication, F(1, 596) = 25.099, p<.001, r = 0.20, and the covariate general liking of winter holidays was also significantly related to attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication, F(1, 596) = 16.069, p<.001, r = 0.16. There was also a significant effect of the type of CSR communication on attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication after controlling for the effects of gender and general liking of winter holidays, F(2, 596) = 12.574, p<.001, partial η² = .04. Planned contrasts revealed that compared with the baseline non-CSR communication, attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication was significantly higher when one-way CSR communication was issued, t(596) = 3.776, p<.001, r = 0.15, and when two-way CSR communication was issued, t(596) = 4.758, p<.001, r = 0.19. Hence, hypothesis 1a is supported. One-way CSR communication and two-way CSR communication do not differ significantly from each other when it comes to improving attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication, t(596) = 1.103, p = .270, r = 0.05. Hypothesis 2a is rejected.

To test our mediation hypothesis, hypothesis 3a, we ran a conditional process analysis using PROCESS 3.0 for SPSS by Hayes (2018). We used model 5, a conditional process model with a single indirect effect of X on Y through M and a direct effect that is a function of W (Hayes 2018, p. 403). X is the multicategorical focal predictor, the type of CSR communication (i.e., non-CSR communication as baseline, one-way CSR communication, and two-way CSR communication), W is the continuous moderator, pro-environmental identity, and M is the continuous mediator, perceived consumer effectiveness. As control variables, gender and general liking of winter holidays were included. Indicator coding of categorical variable X is shown in Table 3.

| Type of CSR Communication | D1 | D2 |

|---|---|---|

| Non-CSR communication (control) | 0 | 0 |

| One-way CSR communication | 1 | 0 |

| Two-way CSR communication | 0 | 1 |

Note: The two dummy variables D1 and D2 represent the three experimental conditions. CSR = corporate social responsibility.

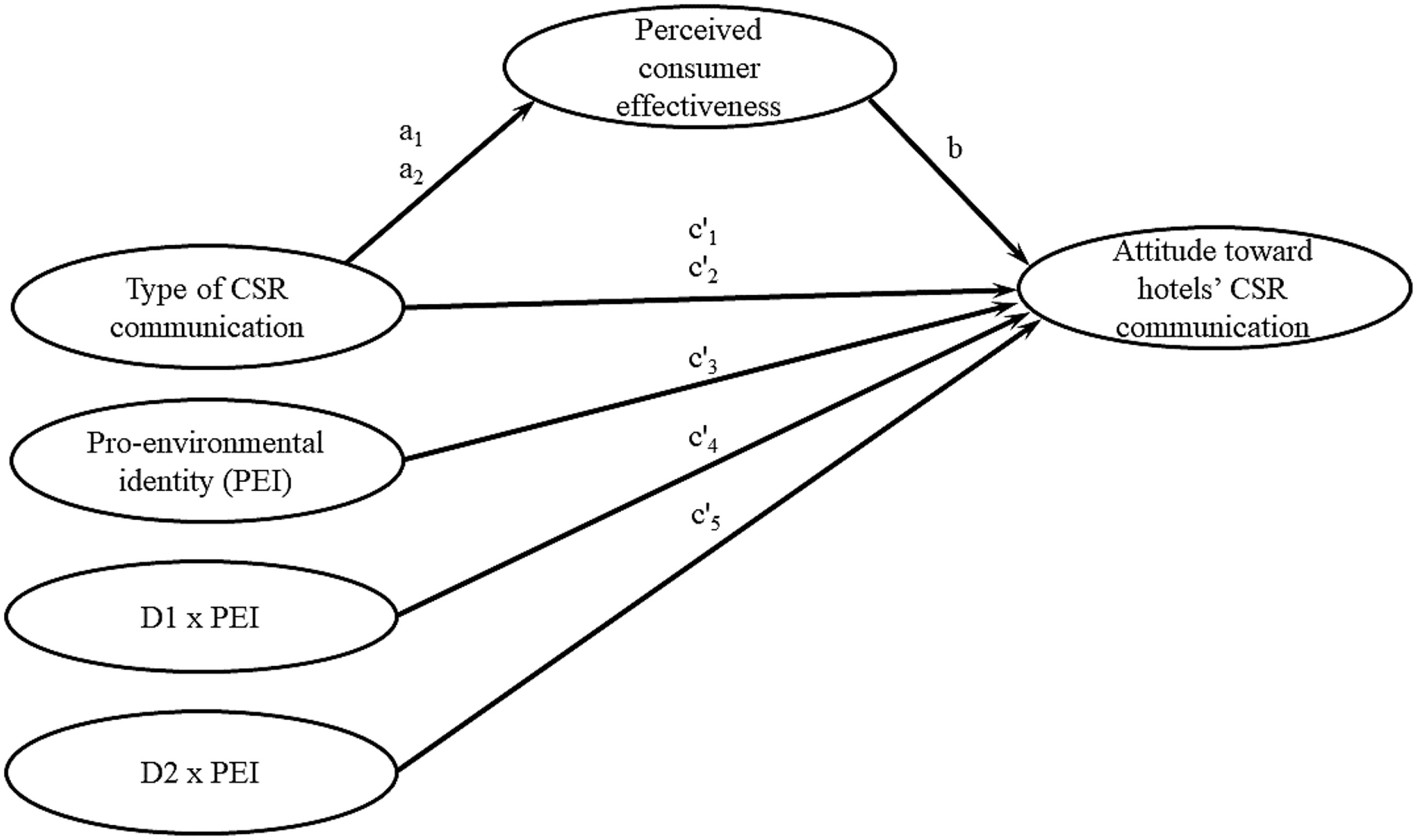

The analysis provides two dummy variables for the respective group comparisons (D1 = comparison of the reference group non-CSR communication and one-way CSR communication; D2 = comparison of the reference group non-CSR communication and two-way CSR communication). Figure 1 presents a diagram of the conditional process model for attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication. The main results of this analysis are presented in Table 4.

| Mediation Model: Perceived Consumer Effectiveness as a Mediator Variable | Full Model: Attitude toward Hotels’ CSR Communication as a Dependent Variable(Conditional Process Model) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coeff. (SE) | p | Coeff. (SE) | p | |||

| D1 | a1 | 0.215(0.131) | .102 | c’1 | 0.388(0.096) | <.001 |

| D2 | a2 | 0.423(0.135) | .002 | c’2 | 0.379(0.099) | <.001 |

| Perceived consumer effectiveness | b | 0.377(0.038) | <.001 | |||

| Pro-environmental identitya | c’3 | 0.283(0.057) | <.001 | |||

| Interaction 1(D1 × pro-environmental identitya) | c’4 | 0.108(0.074) | .145 | |||

| Interaction 2(D2 × pro-environmental identitya) | c’5 | –0.001(0.076) | .989 | |||

| Gender | –0.441(0.109) | <.001 | –0.227(0.080) | .005 | ||

| General liking of winter holidays | 0.137(0.032) | <.001 | 0.038(0.024) | .110 | ||

| Constant | 4.293(0.206) | <.001 | 3.277(0.230) | <.001 | ||

| R² = 0.072,F(4, 596) = 11.571,p < .001 | R² = 0.475,F(8, 592) = 66.953,p < .001 | |||||

Note: Model 5 of PROCESS by Hayes (2018). CSR = corporate social responsibility.

aPro-environmental identity was mean-centered prior to analysis.

The overall conditional process model is significant, F(8, 592) = 66.953, p<.001. The effects of the experimental conditions are derived from their relative effects. Therefore, the contrasting effects of the indicator coded dummy variables (D1 and D2) are addressed in the analysis.

To test the indirect effects (a1b and a2b), a bootstrapping procedure is used that considers the mediating influences across the three experimental conditions. We find no significant relative indirect effect of CSR communication types for D1 (non-CSR communication vs. one-way CSR communication) on attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication through perceived consumer effectiveness, a1b = 0.081, CI [–0.020, 0.188]. However, for D2 (non-CSR communication vs. two-way CSR communication), we find a significant relative indirect effect of CSR communication type on attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication through perceived consumer effectiveness, a2b = 0.159, CI [0.058, 0.268]. The confidence intervals for the indirect effects are based on 10,000 bootstrap samples. Following the results, we can accept hypothesis 3a, because differences in attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication are partially mediated by perceived consumer effectiveness in the case of two-way CSR communication.

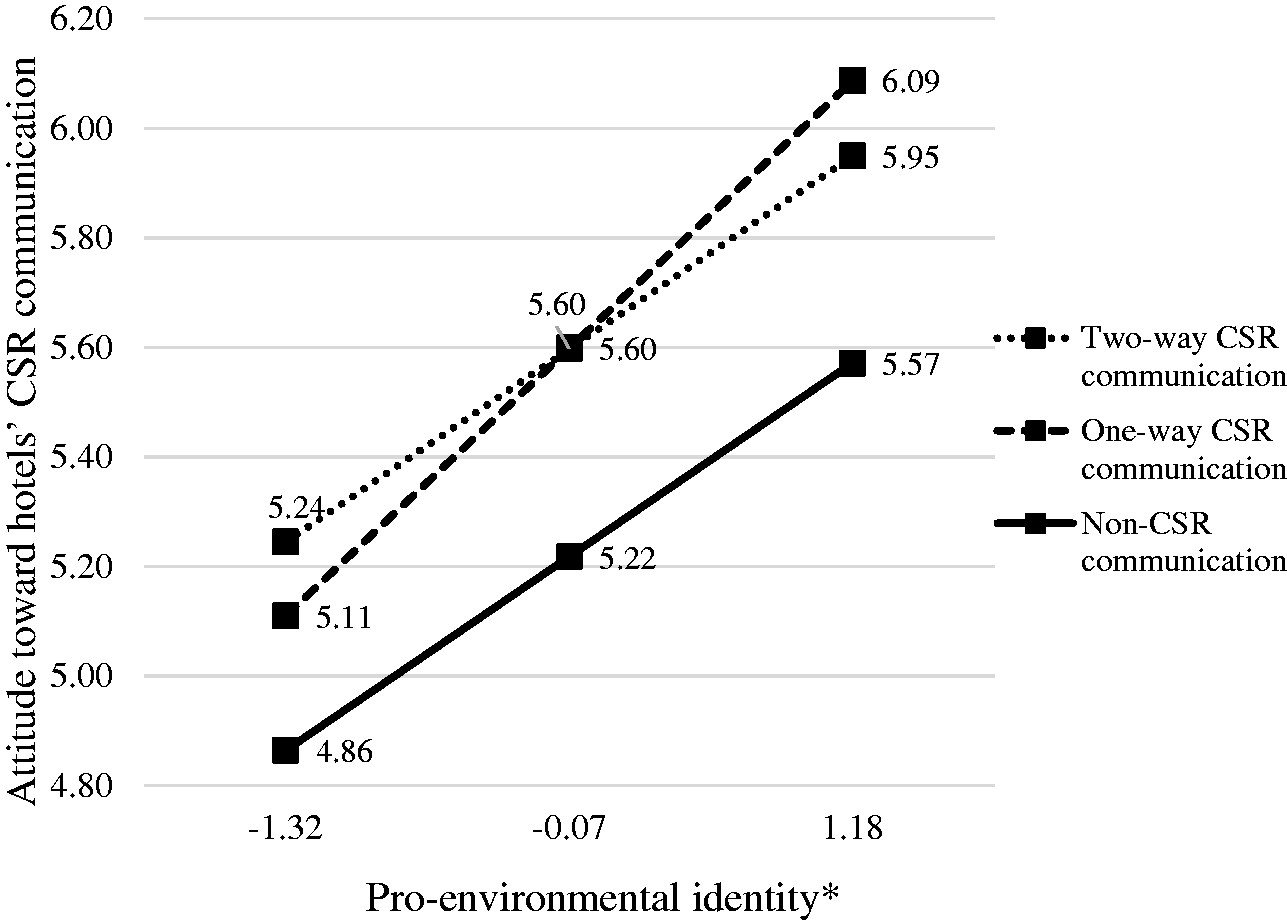

To test hypothesis 4a, we consider the test of the highest-order unconditional interaction for the model with attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication as dependent variable. Results reveal that there is no moderation of CSR communication type by pro-environmental identity, F(2, 592) = 1.347, p = .261. Both dummy variables, that is, comparisons of the reference group non-CSR communication to one-way CSR communication and two-way CSR communication, have no significant interaction effects with pro-environmental identity (see Table 4). Thus, hypothesis 4a must be rejected. Figure 2 shows a plot that visualizes the results for the focal predictor.

Figure 2. Conditional effect of the type of CSR communication on attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication.

*Pro-environmental identity was mean-centered prior to analysis.

Intention to behave unethically

To test hypothesis 1b, we calculated a separate ANCOVA with the type of CSR communication as factor and intention to behave unethically as dependent variable. Again, gender and general liking of winter holidays were included as control variables. While the covariate gender was not significantly related to intention to behave unethically, F(1, 596) = 0.251, p<.617, r = 0.02, the covariate general liking of winter holidays was significantly related to intention to behave unethically, F(1, 596) = 10.600, p = .001, r = 0.13. There was also a significant effect of the type of CSR communication on intention to behave unethically after controlling for the effects of gender and general liking of winter holidays, F(2, 596) = 22.439, p<.001, partial η² = .07. Planned contrasts revealed that compared to the baseline non-CSR communication, intention to behave unethically is significantly lower when one-way CSR communication was issued, t(596) = 4.773, p<.001, r = 0.19, and when two-way CSR communication was issued, t(596) = 6.471, p<.001, r = 0.26. Hence, hypothesis 1b is supported. One-way CSR communication and two-way CSR communication do not differ significantly from each other when it comes to intention to behave unethically, t(596) = 1.861, p = .063, r = 0.08. Hypothesis 2b is rejected.

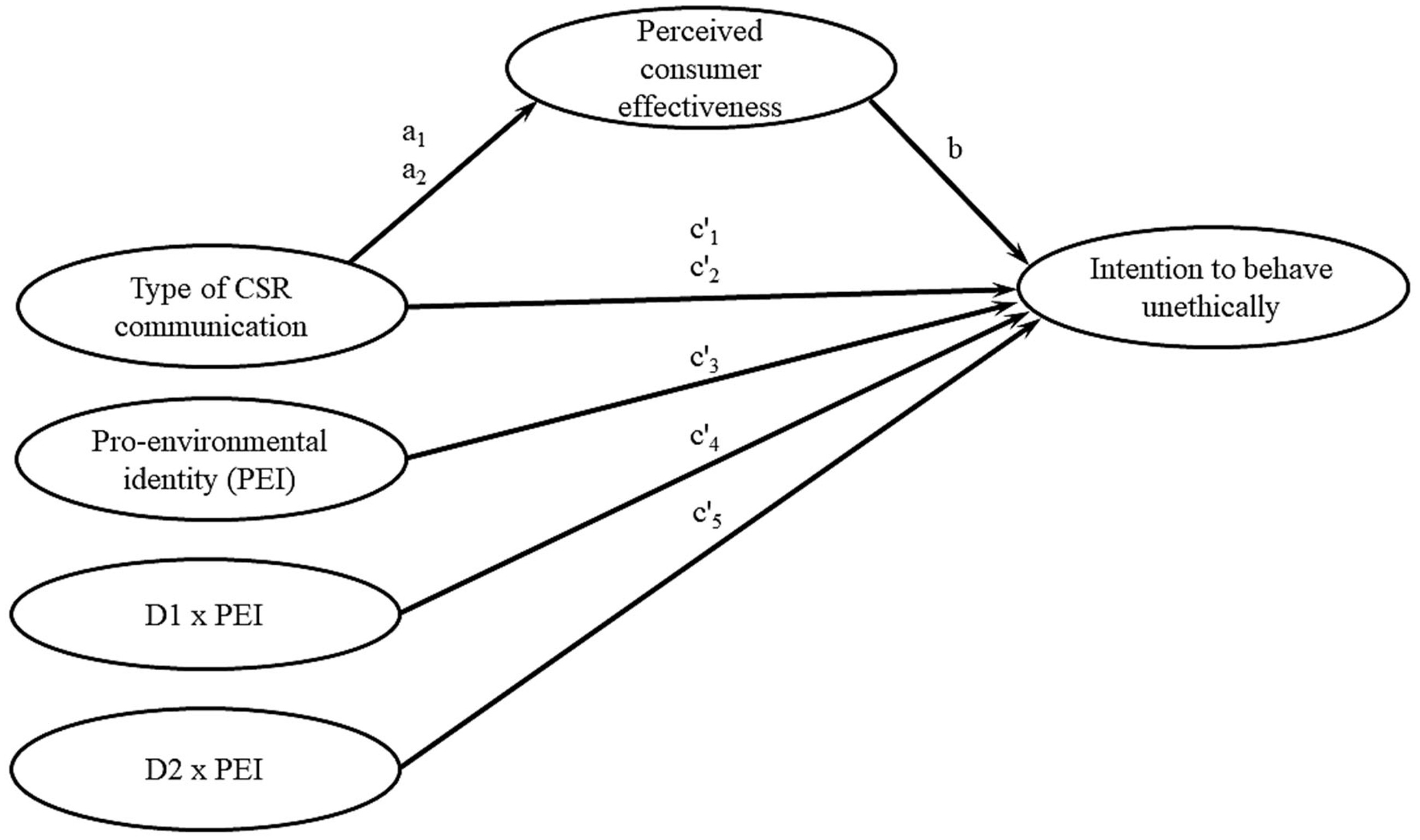

To test the mediation hypothesis, hypothesis 3b, we once more ran a conditional process analysis using PROCESS 3.0 for SPSS by Hayes (2018). We again used model 5, with similar specifications as for attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication. Figure 3 presents a diagram of the conditional process model for the dependent variable intention to behave unethically. The main results of this analysis are presented in Table 5. The overall conditional process model is significant, F(8, 592) = 10.519, p<.001.

| Mediation Model: Perceived Consumer Effectiveness as a Mediator Variable | Full Model: Intention to Behave Unethically as a Dependent Variable (Conditional Process Model) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Coeff. (SE) | p | Coeff. (SE) | p | |||

| D1 | a1 | 0.215(0.131) | .102 | c’1 | –0.592(0.123) | <.001 |

| D2 | a2 | 0.423(0.135) | .002 | c’2 | –0.787(0.127) | <.001 |

| Perceived consumer effectiveness | b | –0.105(0.049) | .031 | |||

| Pro-environmental identitya | c’3 | 0.248(0.073) | <.001 | |||

| Interaction 1(D1 × pro-environmental identitya) | c’4 | –0.329(0.095) | <.001 | |||

| Interaction 2(D2 × pro-environmental identitya) | c’5 | –0.348(0.098) | <.001 | |||

| Gender | –0.441(0.109) | <.001 | 0.021(0.103) | .843 | ||

| General liking of winter holidays | 0.137(0.032) | <.001 | 0.108(0.030) | <.001 | ||

| Constant | 4.293(0.206) | <.001 | 4.576(0.296) | <.001 | ||

| R² = 0.072,F(4, 596) = 11.571,p < .001 | R² = .125,F(8, 592) = 10.519,p < .001 | |||||

Note: Model 5 of PROCESS by Hayes (2018).

aPro-environmental identity was mean-centered prior to analysis.

To test the indirect effects (a1b and a2b), we once again employ a bootstrapping procedure that considers the mediating influences across the three experimental conditions. Once more, we find no significant relative indirect effect of CSR communication types for D1 (non-CSR communication vs. one-way CSR communication) on intention to behave unethically through perceived consumer effectiveness, a1b = –0.023, CI [–0.066, 0.006]. However, for D2 (non-CSR communication vs. two-way CSR communication), we find a significant relative indirect effect of CSR communication type(s) on intention to behave unethically through perceived consumer effectiveness, a2b = –0.044, CI [–0.104, –0.001]. The confidence intervals for the indirect effects are based on 10,000 bootstrap samples. Therefore, hypothesis 3b is supported, since differences in intention to behave unethically are partially mediated by perceived consumer effectiveness in the case of two-way CSR communication.

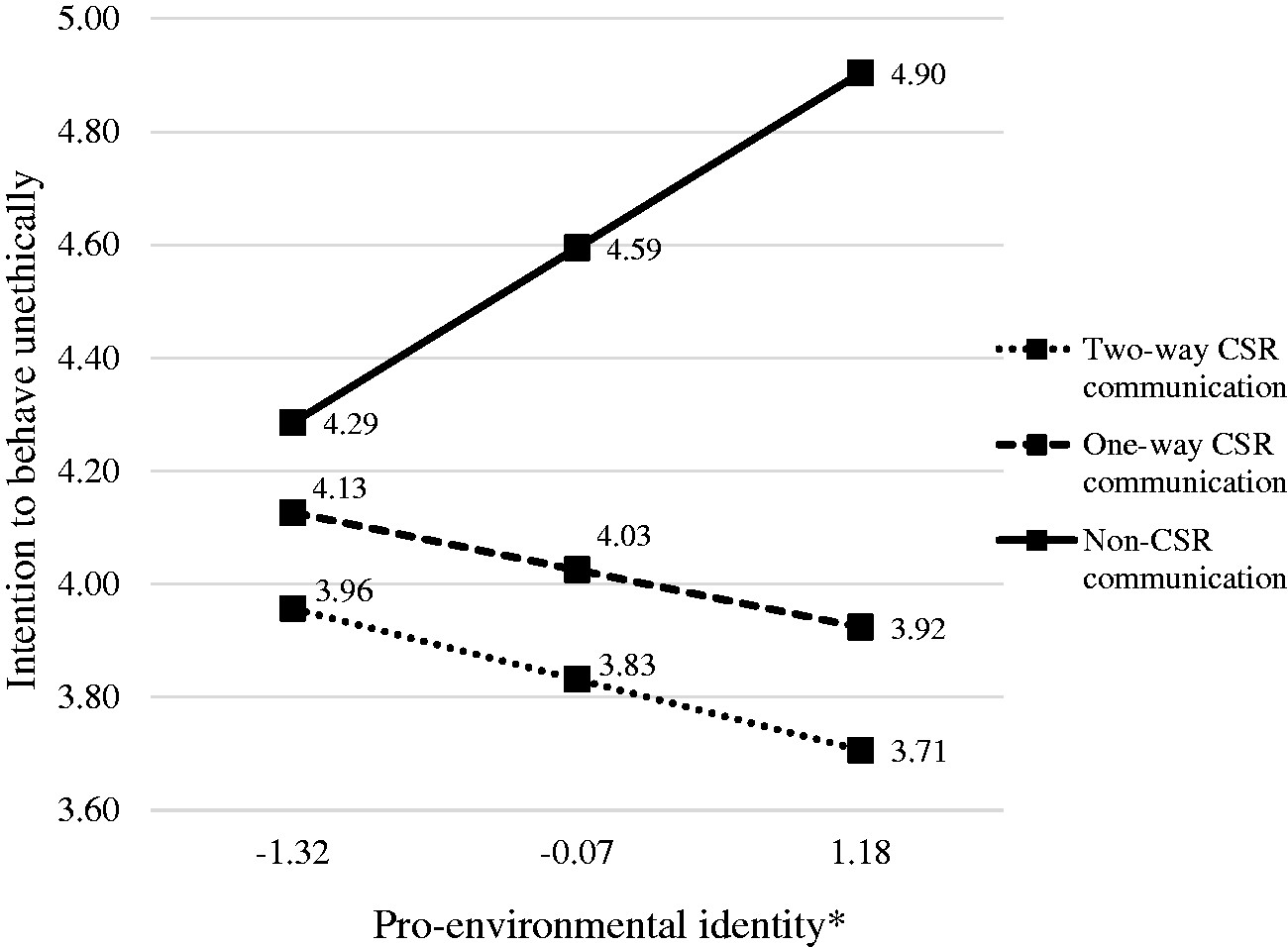

To test hypothesis 4b, we consider the test of the highest-order unconditional interaction. It reveals that the moderation of CSR communication type by pro-environmental identity is significant, F(2, 592) = 8.458, p<.001. Both dummy variables have significant negative interaction effects with pro-environmental identity (see Table 5). This means that when participants with medium to high pro-environmental identity (at these moderator levels, the conditional effects are significant) receive CSR communication as a stimulus, their intention to behave unethically is significantly lower than when participants receive non-CSR communication. Thus, hypothesis 4b is supported. Figure 4 shows a plot that visualizes the conditional effect of the focal predictor.

Figure 4. Conditional effect of the type of CSR communication on intention to behave unethically.

*Pro-environmental identity was mean-centered prior to analysis.

Discussion

Our results show that both one-way CSR communication and two-way CSR communication help improve the attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication and decrease the intention to behave unethically, compared to non-CSR communication. Thus, from the customers’ perspective, we did not find any evidence of consumers preferring greenhushing to hotels’ CSR communication. Our results further indicate that, while the direct comparison of one-way and two-way CSR communications yielded no statistically significant difference, two-way CSR communication is preferable over one-way CSR communication when considering perceived consumer effectiveness as a mediator. Compared to greenhushing, while one-way CSR communication did not significantly increase perceived consumer effectiveness, two-way CSR communication did. Increased perceived consumer effectiveness significantly improved the attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication and significantly mitigated the intention to behave unethically. As predicted by the theory of cognitive dissonance, when customers are empowered through two-way CSR communication and encouraged to be proactively involved in sustainable actions, they see an opportunity to decrease their cognitive dissonance, and thus, change their attitudes and behavioral intentions.

Our findings indicate that while a higher level of pro-environmental identity leads to a more favorable attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication, there is no interaction between pro-environmental identity and the type of CSR communication. This means that pro-environmental identity alone can improve the attitude toward hotels’ CSR communication, regardless of whether individuals receive CSR communication. In contrast, the interaction between the type of CSR communication and pro-environmental identity on intentions to behave unethically was statistically significant.

However, by further investigating the interaction effect between the type of CSR communication and pro-environmental identity on tourists’ intention to behave unethically, we found that, for those individuals who did not receive any CSR communication (greenhushing), a higher level of pro-environmental identity increased the intention to behave unethically. In contrast, the conditional effects of pro-environmental identity on intention to behave unethically for one-way and two-way CSR communication were negative but statistically nonsignificant. At the same time, the two significant negative interaction effects of pro-environmental identity and the type of CSR communication on the intention to behave unethically indicate that the provision of hotels’ CSR communication can mitigate the irresponsible behavioral intentions, particularly among individuals with a higher level of pro-environmental identity. Taken together, these results seem to imply that hotels’ CSR communication could serve as a reminder that mitigates the irresponsible behavioral intentions, particularly for those with a higher level of pro-environmental identity.

General Discussion

Our research makes a contribution to the recent debate on an emerging phenomenon in the hospitality industry, greenhushing. While greenhushing has been primarily discussed from the business owners’ and managers’ perspectives (i.e., Coles et al. 2017; Font, Elgammal, and Lamond 2017), this article addresses this phenomenon from the customers’ perspective. Our findings from study 1 and study 2 seem to show a consistent picture—there appears to be little evidence that justifies greenhushing from the customers’ perspective.

Based on the findings, we can draw several theoretical implications. First, study 1 leads us to conclude that people tend to engage in self-indulgent behavior during their holiday but they are also willing to listen to the hotels about their sustainability actions. Similarly, they do not seem to mind being “reminded” of their own responsible behavior. These qualitative insights served as an initial stepping-stone to a quantitative exploration in study 2.

Second, drawing on the social psychological theory of tourism motivation (Iso-Ahola 1982) and the theory of cognitive dissonance (Festinger 1962), study 2 tried to explain tourists’ mental discomfort resulting from discrepancies between extravagant holiday behavior and everyday beliefs in sustainability. Our experiment showed that CSR communication, as opposed to greenhushing, could lead to more favorable consumer responses and may reduce tourists’ environmentally irresponsible behavior during the vacation. This is because CSR communication helped the participants reduce their cognitive dissonance by improving their feeling about hotels’ CSR activities and attenuating temptation to act irresponsibly. Such reasoning seems consistent with prior research on sustainable tourism (Juvan and Dolnicar 2014; Dolnicar, Knezevic Cvelbar, and Grün 2017).

This thesis was further confirmed when we took into account the participants’ perceived consumer effectiveness through two-way CSR communication—the more empowered the participants felt, the more reluctant they were to engage in socially irresponsible behavior (Akehurst, Afonso, and Martins Gonçalves 2012). If our findings are in line with prior research (Webster Jr. 1975; Ellen, Wiener, and Cobb-Walgren 1991; Antonetti and Maklan 2014; Currás‐Pérez et al. 2018), such empowerment through perceived consumer effectiveness is indeed a strong counterargument to the appropriateness of greenhushing.

Yet, it seems a cautionary note is needed. A recent study found that companies internally practicing CSR but not externally promoting their CSR practices (“discreet” CSR positioning or greenhushing) could produce just as favorable consumer outcomes (i.e., consumers’ attributions to hotels’ CSR motivation and purchase intentions) as companies internally practicing CSR and externally communicating their CSR practices (“uniform” CSR positioning) (Ginder, Kwon, and Byun, forthcoming). On this basis, the authors conclude that companies would be better off to employ “a more discreet and modest approach to CSR communication, rather than directly utilizing their CSR practices in marketing or PR” (n.p.), corroborating Font, Elgammal, and Lamond’s (2017) and Coles et al.’s (2017) managerial positions.

Third, the investigation of pro-environmental identity provided additional important insights. It is not surprising that two-way CSR communication reminds customers of their responsibility and provides avenues for behaving more responsibly during the holiday stay. What is surprising is that, for the non-CSR communication group, the effect of pro-environmental identity on intentions to behave unethically is positive and significant. That is, when the levels of pro-environmental identity increase, the intention to behave unethically also rises. One possible interpretation is that, during the holiday, pro-environmental identity is subdued by self-indulgence until it is activated by some form of external communication. Therefore, in our study context, it is when customers receive CSR communication that their pro-environmental identity is triggered or “switched on,” leading to more responsible behavior. This interpretation seems consistent with a recent study that found that consumers may be unaware of their pro-environmental attitudes when making travel purchase decisions, but “can be made aware through environmental cues” (Kim, Tanford, and Book 2020, forthcoming). Needless to say, this interpretation needs further scrutiny with thorough empirical testing.

Fourth, somewhat surprising was our finding that two-way CSR communication was not superior to one-way CSR communication in terms of improving attitudes toward hotels’ CSR communication and decreasing intentions to behave unethically. A possible interpretation may be that an alternative effect might have counteracted the hypothesized effect. Perhaps, two-way CSR communication makes guests feel that the hotel is trying to control their behavior or restrict their freedom, leading to a feeling of reactance toward the message (Johnstone and Tan 2015). If this is the case, one-way CSR communication might be “enough” to encourage the guests’ sustainable behavior as it is more implicit or less direct. Yet, this interpretation needs further empirical scrutiny in the future.

This research also provides some managerial implications for hospitality industry practitioners. We found a positive relationship between pro-environmental identity and intention to behave unethically only for the non-CSR communication group. While this effect might need to be explored further in future studies, it still points toward the fact that any CSR communication is beneficial for hotels. Dolnicar and Grün (2009) suggest that only attracting those customers with high pro-environmental identity might be the better strategy compared to educating customers and motivating them to behave responsibly. However, this strategy is not a viable solution for the industry in its entirety. Our society as a whole, including tourism and hospitality sections, is becoming more and more conscious of environmental issues, aiming at our sustainable future. Targeting only those with a higher level of pro-environmental identity goes against this direction, that is, global sustainable development. It is therefore essential that, regardless of individual levels of pro-environmental identity, people should be reminded, guided, and motivated to behave responsibly while on holiday. This will ultimately allow a positive and healthy growth of the industry.

In this light, the use of two-way CSR communication seems particularly advantageous when guests are already engaged in some pro-environmental activities in their everyday lives. Through this route, accommodation businesses should try to involve their guests in the CSR activities and provide possibilities for socially responsible actions. If the guests are aware of their potential contribution, their positive reactions are accentuated.

Limitations and Suggestions for Further Research

As with any empirical work, our research should recognize a few important limitations. First, study 1’s findings must be treated with care. The focus group is a qualitative research method, and therefore, the insights based on selected verbatim responses must not be generalized. By the same token, we tried to minimize social desirability bias by asking the respondents to be honest and critical throughout the focus group sessions. Moreover, we also employed a third-person technique—when we felt that participants were reluctant to talk about their own experience, we asked about their observations of others behaving irresponsibly on holiday. Nevertheless, the risk of social desirability bias remains.

Second, our study 2 may have suffered from self-report bias. Our experiment used three hypothetical situations, under which we only asked for behavioral intentions. Thus, the findings relied on the individuals’ own report of “intention” but no actual behavior was observed. Similarly, we should recognize the possibility of self-representation bias in the results. Most people tend to regard themselves as good persons. Thus, our respondents may have welcomed CSR communication that could contribute to being a good citizen.

Third, in both studies, our participants consisted of the residents of a central European country. Our findings should therefore be interpreted in this cultural context. The two key studies on greenhushing, Font, Elgammal, and Lamond (2017) and Coles et al. (2017), were both based on hotel owners and managers in rural areas of the United Kingdom. Thus, there might have been important cultural factors that influenced the findings.

Besides overcoming the aforementioned limitations, the present research should foster future research in several ways. First and foremost, we should further scrutinize the phenomenon of greenhushing from the customer’s perspective in terms of:

•

how consumers distinguish greenhushing (undercommunicating of CSR activities while companies are actually practicing CSR) from non-CSR communication (not communicating CSR activities because companies are not practicing CSR); in other words, whether consumers perceive greenhushing differently when they are aware or unaware of the businesses’ CSR activities;

•

whether consumers’ reactions would be the same if we consider two types of greenhushing: (1) undercommunicating of CSR activities that companies practice and (2) undercommunicating of CSR activities that companies require their customers to practice;

•

what type of consumers are more susceptible to greenhushing; and

•

whether individuals with no desire to hear sustainability reminders can respond positively to CSR communication when receiving it.

We strongly believe that addressing these questions could respond to somewhat conflicting findings between the present study and Ginder, Kwon, and Byun (forthcoming), and should significantly advance our limited knowledge on greenhushing from the customers’ perspective.

Next, unlike our scenario-based approach, future research should conduct a field experiment in collaboration with the industry in a real setting. Also, we addressed our hypotheses in a specific setting, that is, winter ski and spa holiday. While this was a very common and familiar setting for the participants in this study, future research should test different holiday contexts, such as summer beach, safari adventure, city breaks, historical tour, etc. Finally, future research should address how widespread greenhushing has become. In so doing, we should also examine how people perceive greenhushing in different parts of the world, especially in non-European regions, such as Asia, Africa, or South America.

Acknowledgments

We thank three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions during the review process. We also appreciatively acknowledge Professor Xavier Font's valuable insights that helped significantly improve the contributions of this article.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

Andrea Ettinger https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0600-1931

References

Akehurst Gary, Afonso Carolina, Martins Gonçalves Helena. 2012. “Re-examining Green Purchase Behaviour and the Green Consumer Profile: New Evidences.” Management Decision 50 (5): 972–88.

Antonetti Paolo, Maklan Stan. 2014. “Feelings That Make a Difference: How Guilt and Pride Convince Consumers of the Effectiveness of Sustainable Consumption Choices.” Journal of Business Ethics 124 (1): 117–34.

Barr Stewart, Shaw Gareth, Coles Tim. 2011. “Sustainable Lifestyles: Sites, Practices, and Policy.” Environment and Planning A 43 (12): 3011–29.

Batra Rajeev, Keller Kevin L. 2016. “Integrating Marketing Communications: New Findings, New Lessons, and New Ideas.” Journal of Marketing 80 (6): 122–45.

Biddle Bruce J., Bank Barbara J., Slavings Ricky L. 1987. “Norms, Preferences, Identities and Retention Decisions.” Social Psychology Quarterly 50 (4): 322–37.

Bigné Enrique J., Mattila Anna S., Andreu Luisa. 2008. “The Impact of Experiential Consumption Cognitions and Emotions on Behavioral Intentions.” Journal of Services Marketing 22 (4): 303–15.

Bojanic David C., Warnick Rodney B. 2019. “The Relationship between a Country’s Level of Tourism and Environmental Performance.” Journal of Travel Research 59 (2): 220–230.

Brønn Peggy S., Vrioni Albana B. 2001. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Cause-Related Marketing: An Overview.” International Journal of Advertising 20 (2): 207–22.

Bruijn Kim, de Rob, Dirven Eke, Eijgelaar, Peeters Paul. 2013. “Travelling Large in 2012: The Carbon Footprint of Dutch Holidaymakers in 2012 and the Development Since 2002.” https://www.cstt.nl/userdata/documents/cstt2013_travellinglargein2012_lowres.pdf.

Buckley Ralf. 2018. “Measuring Sustainability of Individual Tourist Behavior.” Journal of Travel Research 58 (4): 709–10.

Budeanu Adriana. 2007. “Sustainable Tourist Behaviour—A Discussion of Opportunities for Change.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 31 (5): 499–508.

Carfora Valentina, Caso Daniela, Sparks Paul, Conner Mark. 2017. “Moderating Effects of Pro-environmental Self-Identity on Pro-environmental Intentions and Behaviour: A Multi-behaviour Study.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 53:92–99.

Carlos W. C., Lewis Ben W. 2018. “Strategic Silence: Withholding Certification Status as a Hypocrisy Avoidance Tactic.” Administrative Science Quarterly 63 (1): 130–69.

Carr Neil. 2002. “The Tourism–Leisure Behavioural Continuum.” Annals of Tourism Research 29 (4): 972–86.

Caruana Robert, Glozer Sarah, Crane Andrew, McCabe Scott. 2014. “Tourists’ Accounts of Responsible Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 46:115–29.

Christensen P. N., Rothgerber Hank, Wood Wendy, Matz David C. 2004. “Social Norms and Identity Relevance: A Motivational Approach to Normative Behavior.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 30 (10): 1295–309.

Coles Tim, Warren Neil, Borden D. S., Dinan Claire. 2017. “Business Models among SMTEs: Identifying Attitudes to Environmental Costs and Their Implications for Sustainable Tourism.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25 (4): 471–88.

Cook, Andrew J., Geoff N. Kerr, Kevin Moore. 2002. “Attitudes and Intentions towards Purchasing GM Food.” Journal of Economic Psychology 23 (5): 557–72.

Currás-Pérez Rafael, Dolz-Dolz Consuelo, Miquel-Romero María J., Sánchez-García Isabel. 2018. “How Social, Environmental, and Economic CSR Affects Consumer‐Perceived Value: Does Perceived Consumer Effectiveness Make a Difference?” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25 (5): 733–47.

Dann Graham, Cohen Erik. 1991. “Sociology and Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 18 (1): 155–69.

Del Chiappa Giacomo, Grappi Silvia, Romani Simona. 2016. “Attitudes toward Responsible Tourism and Behavioral Change to Practice It: A Demand-Side Perspective in the Context of Italy.” Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism 17 (2): 191–208.

Delmas Magali A., Burbano Vanessa C. 2011. “The Drivers of Greenwashing.” California Management Review 54 (1): 64–87.

Dermody Janine, Hanmer-Lloyd Stuart, Koenig-Lewis Nicole, Zhao Anita L. 2015. “Advancing Sustainable Consumption in the UK and China: The Mediating Effect of Pro-environmental Self-Identity.” Journal of Marketing Management 31 (13/14): 1472–502.

Dermody Janine, Koenig-Lewis Nicole, Zhao Anita L., Hanmer-Lloyd Stuart. 2018. “Appraising the Influence of Pro-environmental Self-Identity on Sustainable Consumption Buying and Curtailment in Emerging Markets: Evidence from China and Poland.” Journal of Business Research 86:333–43.

Devinney Timothy M., Auger Pat, Eckhardt Giana, Birtchnell Thomas. 2006. “The Other CSR: Consumer Social Responsibility.” Stanford Social Innovation Review Fall.

Diehl Sandra, Terlutter Ralf, Mueller Barbara. 2016. “Doing Good Matters to Consumers: The Effectiveness of Humane-Oriented CSR Appeals in Cross-Cultural Standardized Advertising Campaigns.” International Journal of Advertising 35 (4): 730–57.

Dolnicar Sara, Grün Bettina. 2009. “Environmentally Friendly Behavior: Can Heterogeneity among Individuals and Contexts/Environments Be Harvested for Improved Sustainable Management?” Environment and Behavior 41 (5): 693–714.

Dolnicar Sara, Knezevic Cvelbar Ljubica, Grün Bettina. 2017. “Do Pro-environmental Appeals Trigger Pro-environmental Behavior in Hotel Guests?” Journal of Travel Research 56 (8): 988–97.

Ellen Pam S., Wiener Joshua L., Cobb-Walgren Cathy. 1991. “The Role of Perceived Consumer Effectiveness in Motivating Environmentally Conscious Behaviors.” Journal of Public Policy & Marketing 10 (2): 102–17.

Ettinger Andrea, Grabner-Kräuter Sonja, Terlutter Ralf. 2018. “Online CSR Communication in the Hotel Industry: Evidence from Small Hotels.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 68:94–104.

European Commission. 2011. “Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. A Renewed EU Strategy 2011-14 for Corporate Social Responsibility.” https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri = CELEX:52011DC0681&from = EN.

Festinger Leon. 1962. A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Font Xavier, Elgammal Islam, Lamond Ian. 2017. “Greenhushing: The Deliberate under Communicating of Sustainability Practices by Tourism Businesses.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25 (7): 1007–23.

Ganglmair-Wooliscroft Alexandra, Wooliscroft Ben. 2017. “Ethical Behaviour on Holiday and at Home: Combining Behaviour in Two Contexts.” Journal of Sustainable Tourism 25 (4): 589–604.

Ginder Whitney, Kwon Wi-Suk, Byun Sang-Eun. Forthcoming. “Effects of Internal–External Congruence-Based CSR Positioning: An Attribution Theory Approach.” Journal of Business Ethics.

Gnoth Juergen. 1997. “Tourism Motivation and Expectation Formation.” Annals of Tourism Research 24 (2): 283–304.

Gössling Stefan, Garrod Brian, Aall Carlo, Hille John, Peeters Paul. 2011. “Food Management in Tourism: Reducing Tourism’s Carbon ‘Foodprint.’” Tourism Management 32 (3): 534–43.

Gössling Stefan, Scott Daniel, Hall C. M., Ceron Jean-Paul, Dubois Ghislain. 2012. “Consumer Behaviour and Demand Response of Tourists to Climate Change.” Annals of Tourism Research 39 (1): 36–58.

Grewal Rajdeep, Mehta Raj, Kardes Frank R. 2000. “The Role of the Social-Identity Function of Attitudes in Consumer Innovativeness and Opinion Leadership.” Journal of Economic Psychology 21 (3): 233–52.

Grosbois Danuta de. 2012. “Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting by the Global Hotel Industry: Commitment, Initiatives and Performance.” International Journal of Hospitality Management 31 (3): 896–905.

Hayes Andrew F. 2018. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. New York: Guilford.

Iso-Ahola Seppo E. 1982. “Toward a Social Psychological Theory of Tourism Motivation: A Rejoinder.” Annals of Tourism Research 9 (2): 256–62.

Johnstone Micael-Lee, Tan Lay P. 2015. “Exploring the Gap between Consumers’ Green Rhetoric and Purchasing Behaviour.” Journal of Business Ethics 132 (2): 311–28.

Jordan Jennifer, Mullen Elizabeth, Murnighan J. K. 2011. “Striving for the Moral Self: The Effects of Recalling Past Moral Actions on Future Moral Behavior.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 37 (5): 701–13.

Juvan Emil, Dolnicar Sara. 2014. “The Attitude–Behaviour Gap in Sustainable Tourism.” Annals of Tourism Research 48:76–95.

Juvan Emil, Dolnicar Sara. 2017. “Drivers of Pro-Environmental Tourist Behaviours Are Not Universal.” Journal of Cleaner Production 166:879–90.

Kang Jiyun, Liu Chuanlan, Kim Sang-Hoon. 2013. “Environmentally Sustainable Textile and Apparel Consumption: The Role of Consumer Knowledge, Perceived Consumer Effectiveness and Perceived Personal Relevance.” International Journal of Consumer Studies 37 (4): 442–52.